In this issue of Q FWE’s What’s Floatin’, we drilldown on South Korea’s offshore wind market including our perspective on current momentum, the region’s strengthening market potential, engagement of key players and the government’s ambition to meet their renewables goal.

Last year saw increased interest in South Korea offshore wind fired by the Government’s Renewable Energy 3020 (20% renewable by 2030) Implementation Plan. New MOUs and/or JVs were announced almost weekly and some parties expressed unsolicited interest in developing floating wind projects, notably Macquarie’s Green Investment Group with partner Gyeongbuk FOWP and also South Korea Engineering & Construction (SK E&C), each for a 1.2GW park. The Ministry of Transport (MOTIE) then announced there would only be one floating park of 1GW, the current maximum spare capacity of the grid, as part of the country’s short-term 4GW renewables goal.

The City of Ulsan recently made formal announcements on the signing of independent MOU’s with four consortia:

• Royal Dutch Shell and CoensHexicon (JV between Korean COENS and Swedish Hexicon)

• KFWind, Korea Floating Wind a JV between WPK (Wind Power Korea) and Principle Power Inc.

• SK E&C and CIP (Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners)

• Macquarie’s GIG (Green Investment Group)

These consortia are invited to each develop a 200MW ‘demonstrator’ project, but really this is commercial size beyond doubt. They will deploy their Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) units soon and a true demonstrator of 750kW will be installed this year, developed by University of Ulsan, Mastek, Unison and Seho at a $15M investment. That is $20 million per full MW, a long way from the country’s 2030 target of just $3 million/MW.

One week after the ‘Ulsan’ projects was announced, KNOC and Equinor voiced their plans to develop the ‘Donghae’ project, to be built around the existing KNOC-owned gas platform that is to be retired in 2020.

Project economics & choice of floater

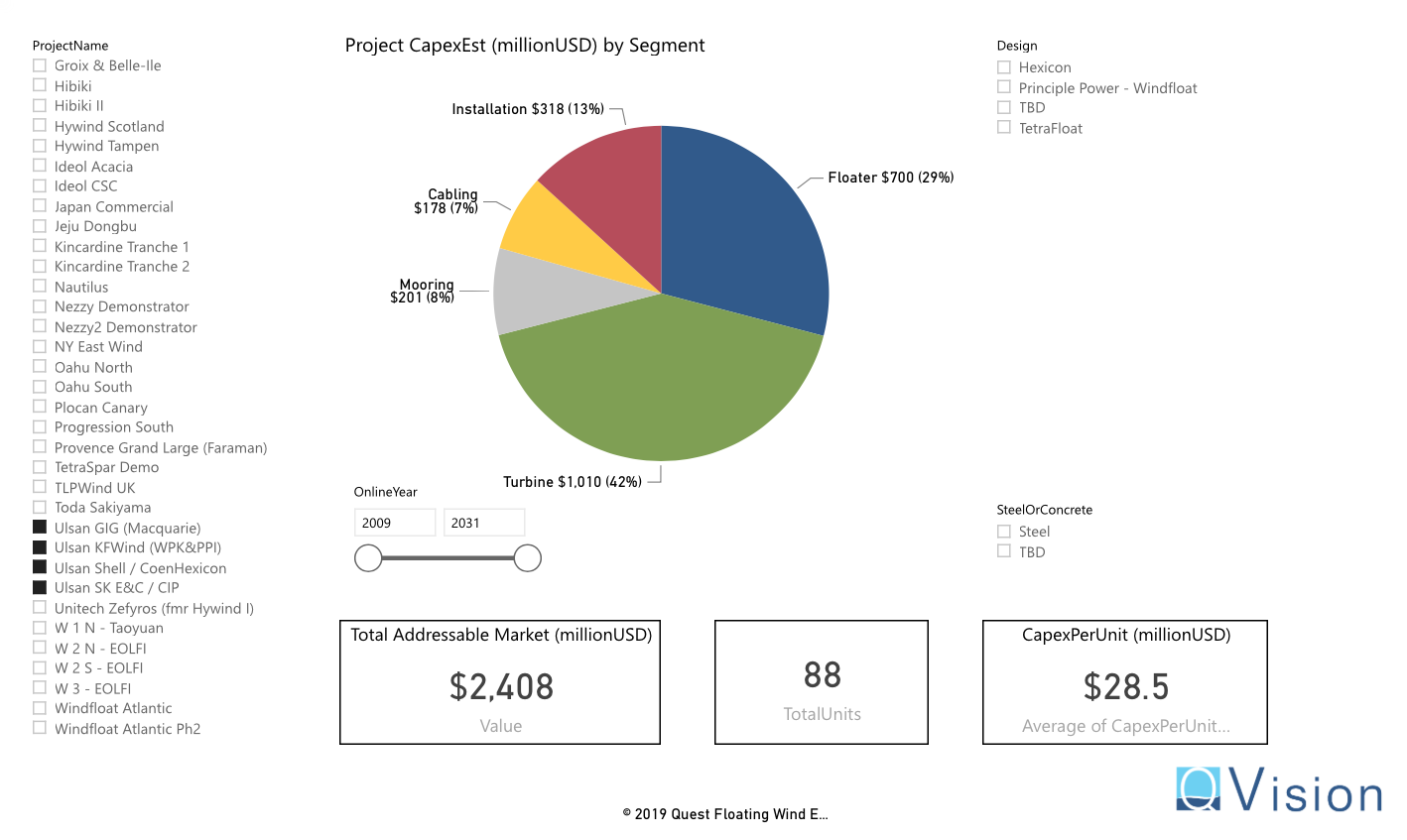

In 2018, South Korea had already pointed the budget for the first stage floating wind at 1.5 trillion WON, approx. $1.3 billion USD¬, being allocated for the first 50 floaters or 500MW capacity. This runs to ~$26 million per Floating Turbine Unit (FTU) or a CapEx of ~$2.6 million/MW which meets the country’s aforementioned economic goal well ahead of schedule.

Notably, an immediate question is which floaters will be utilized for these projects and whether any or all of these will be able to match the goal. As the first two parties in the Ulsan projects are clearly floater concept-linked, this may not prove too hard. The Hexicon floater comes with the Shell/CoensHexicon group and PPI’s Windfloat with the KFWind group. The remaining two are so called ‘floater agnostic’, claimed not to be linked directly to any technology. But isn’t Macquarie linked to Ideol in Asia through its Acacia deal in Japan? And isn’t CIP in a way linked to the Stiesdal TetraSpar?

Right or not, it is interesting to put these four in line, so we put the Q Vision CapEx/MW data module to work, using ‘historical’ data for each floater which reveals that the CapEx for pre-commercial projects runs around the $50 million CapEx per FTU figure. That is a long way from the budget available, but once allocated¬ 8MW turbines, inputting the Ulsan location and full-scale project figures, the model yields a figure much closer to the $26 million CapEx per FTU target, one even pushing that boundary.

Market data

To recap, these developments are a significant step towards the evaluation of floating wind’s competitiveness. Notably, the FWE industry is making its economic case in South Korea. If the South Korea 2030 target of $3 million/MW comes in reach 10 years early, likewise the LCoE of the floating industry may have come down more than some would like us to believe. Then the often mentioned 2030 target of ~$50/MWh could perhaps also come 10 years early. Or sooner.

Erik Rijkers

Quest Floating Wind Energy, LLC

What’s Floatin’